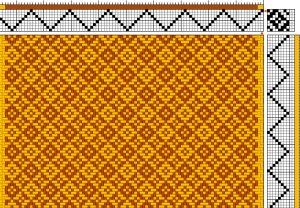

Every now and then I get the urge to make a small inkle band using my Ashford Inklette loom:

This loom is pretty affordable and great to do some small weavings when you want to have something you can take with you easily. I wanted to weave something at this year’s MSKR (Men’s Spring Knitting Retreat) 2012, and though I could have taken my rigid heddle loom, I went for ultra, ultra portable.

What I am ultimately making these bands for – beats me. I just make them.

It’s funny how I wove two or three trouble free bands and then all of the sudden, errors kept coming up all on the same project.

First, if I leave an inkle band in mid warp, I tie the active yarn several times around the bottom peg to maintain the tension until I continue. Well I had done that but when I returned, I continued warping without realizing I still had the wraps around the peg. I finished warping and then realized those loops were still there, preventing me from sliding the band around.

My solution was to carefully, slip the warp threads ahead of the problem off and hold them under tension while I took off all of those wraps. I then, again carefully, placed back all of the warp threads in my hand.

Great, except now one of my warp threads was super loose. I decided the best fix for this was to cut that loop and tie it to the adjacent warp thread very tightly. Even after doing so, I still found it too lose so I resorted to the next best logical solution…

…scotch tape.

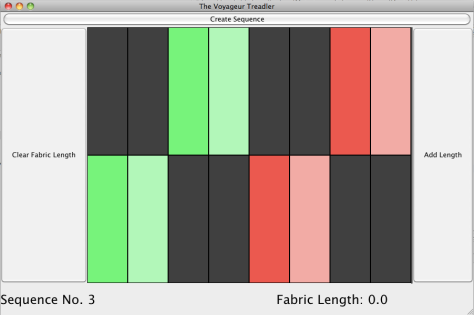

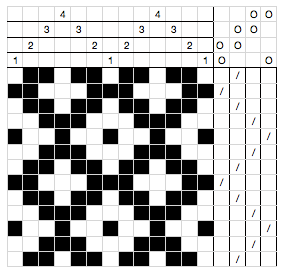

Then I was weaving happily along when a middle heddle flew off! I guess it wasnt tied all that well. Here I separated the warp as much as I could, loosened the tension, and tried to slip a new yarn in just the right position and tie the new heddle down. Here it is in mid repeair:

I can just say that the space I had to work in wasn’t very generous, but I did manage it somehow. Its still not tight but hopefully I can continue to the end with no further issues.

The lesson is, even when things go wrong, at least you get the opportunity to try learning how to fix them and know what to look out for the next time around. It’s the only way to become really good at your craft.